Before You Do Something Permanent, Know About Growth Plates

Before you do something that could impact your puppy’s growth pattern (like an early spay/neuter, or physical activity that’s too vigorous), you should know when the growth plates close on an average puppy.

Growth plates, also known as the epiphyseal plates or physis, are “zones” of cartilage that exist at the end of bones in both canine and humans as each grows older. They contain rapidly dividing cells that allow bones to become longer until the end of puberty in both humans and canines. Growth plates gradually thin as hormonal changes approaching puberty signal the growth plates to close, and in most puppies, this is around the age of approximately 18 months old. At that point, the plates “close” because they’ve contributed all they can to the growth of the bones. The growth plate becomes a stable, inactive, part of the bone, but before then, the plates are soft and vulnerable to injury. An injury to the growth plate might not heal properly, nor heal in time for a puppy to grow up straight and strong. Such an injury can result in a misshapen or shortened limb, and that in turn can create an incorrect angle to a joint which can make the puppy more prone to even more injuries when he grows up.

But what about neutering a dog? How that that impact a growth plate?

Part of the responsibility of sex hormones is to regulate growth. When the sex hormones are removed, growth hormones are missing important regulatory input and the bones continue to grow longer than they ought to. Growth plates lay down bone as a puppy develops and, as it builds bone, the bone becomes longer and the puppy gets larger and taller. Once maturity is reached, this growth plate turns into bone and the puppy’s full height is reached. Most breeders can spot the difference between an intact dog and a dog neutered too young, and studies have proved it to be true (Salmeri et al, JAVMA 1991).

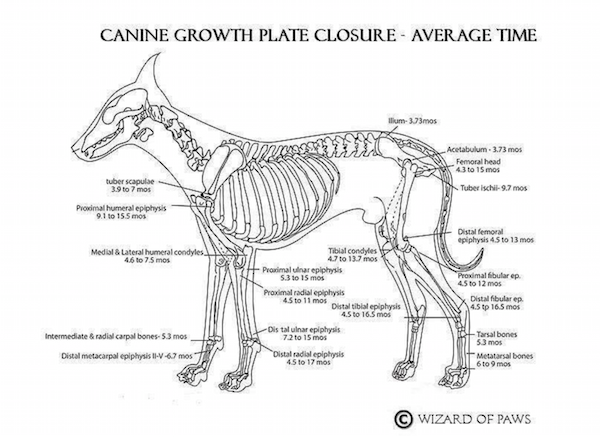

We have the kind permission of Deb Gross to share this fabulous chart, but we ask that you include the following links if you’re going to share it. Click here to see a larger size.

Chart by Deb Gross of Wizard of Paws

Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/

http://